We Remember the Cemeteries!

Documentary Evidence about Jewish Cemeteries for Studying Youth

Cemeteries Documentation

Fact Sheet for Visiting Youth to Jewish Cemeteries

T

he land of Poland is soaked in the blood of the Jewish people who perished in the Holocaust, a nation that lived on its land for a thousand years, who created a culture and set of values, who established communities, public institutions, mutual help organizations, educational and cultural institutions and a thriving economy.T

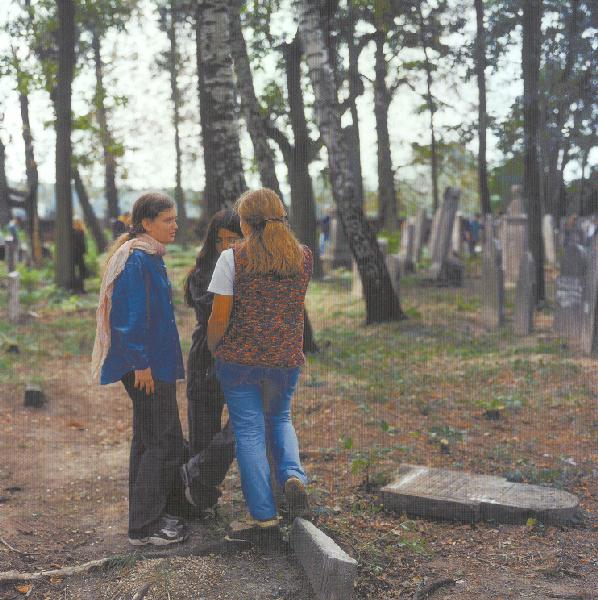

he youth who tour Poland feel and breathe the past, but come across few real vestiges of their people beyond several monuments and a few museums, with a similar number of anti-Semitic posters and graffiti in the streets, riling against a Jewish people who are no longer there. Those who reach the cemeteries that still remain must realize that they are the most prominent physical remnant of the Jews in Poland and from this realization follows the importance of the cemeteries, as a symbol and sign for many future generations.T

he information presented herewith is intended for those youth traveling to Poland who visit the Jewish cemeteries - to aid them in becoming accustomed to the surroundings, in fathoming the symbols and to facilitate the documentation process at the cemetery, if they so desire. The destiny of the few vestiges found today at the cemeteries is fated to disappear, due to natural and human causes, and the element of time.D

uring the Holocaust and in its aftermath most of the cemeteries were deliberately destroyed by anti-Semites and foremost among them, the German occupiers. Even after the war, the destruction of the Jewish cemeteries and the removal of gravestones continued, fed by residents seeking profit, who stole the stones for private purposes, especially for the manufacture of marble. Today, most of the cemeteries have no gravestones of valuable stones, and occasionally even simple gravestones are stolen from the Jewish cemeteries, for use as raw material for new gravestones and for other uses.N

ature itself also battles against the existence of the cemeteries: winds and rain, storms and lightning, wild plants and unruly growth, mainly of tree roots, wreck and uproot the gravestones. The wild undergrowth inhibits access to some of the gravestones.W

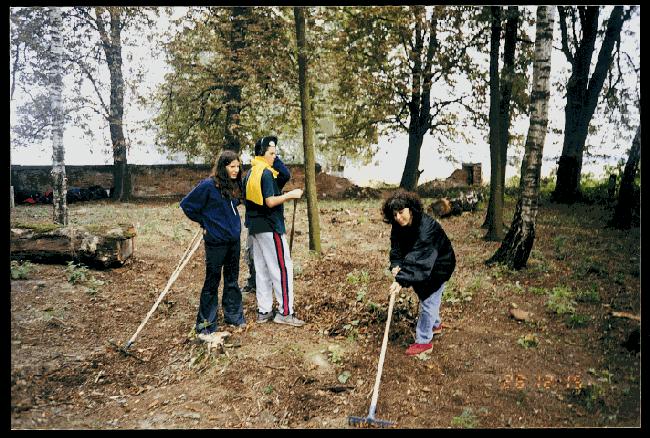

e must mention that, in recent years, alongside these occurrences, various local and international groups have become actively involved in preserving and improving the condition of the Jewish cemeteries. However, despite these efforts, the future of the cemeteries remains in doubt. The pace of natural and unnatural deterioration grows with the years.T

he most effective and realistic way to preserve the historical and cultural value of the cemeteries for future generations is through their documentation. In recent years, various groups have been active in documenting the Jewish cemeteries through photography and transcription, through the publication of research and books, and lately, through the dissemination of information on the Internet.T

his is a holy task, to bestow dignity to those who are buried there. After the destruction of the community, there is no one left to visit the graves of their forefathers. In this way, we honor and commemorate the memory of the destroyed community - and perhaps even more importantly, we create a channel of communication to coming generations and to those who seek their family roots, the latter whose number has been growing in recent years all over the world.T

he addition of documentation tasks at the cemeteries to the visits of Jewish youth to Poland can contribute much to this goal and add an active side to the mission.B

elow are a number of explanations and words of advice to interested youth.

The Cemeteries of Poland

E

ach Jewish community aspired to the founding of a cemetery, often even before the synagogue was built. This involved receiving permission from the government and acquiring the land. Sometimes great expenditures of time and money were necessary. However, there are known cases where a ruler who desired the development of a local Jewish community would assist them and even contribute part of the land to establish a cemetery.T

he cemeteries would be set up in the vicinity of the Jewish community and today some may be found in the center of the town; there are other places where the Jewish cemetery is isolated and distant from the center of the settlement, and transportation is problematic and difficult.A

ccording to the law observed today in Poland, the ownership of the Jewish cemeteries is in the hands of one of nine religious Jewish communities officially recognized and listed according to law in Poland.A

ccording to a previous law, the ownership of the cemeteries was in the hands of the local government and under the official supervision of the "Regional Conservator of Cultural Assets." In actuality, the nine listed Jewish communities have no connection to most of the cemeteries throughout the country.A

t a number of sites, the subject of a Jewish cemetery is important to the local residents. I have met with such people, and with historians and leaders of the local municipality, who are willing to lend a hand, and there are those who willingly invest their energies in this regard.

T

he Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, and those who head it, devote energy, attention and much work to the subject of the Jewish cemeteries in PolandThe Conditions of the Jewish Cemeteries Today

T

he cemeteries or that part of them that remain are generally neglected, do not receive regular maintenance, and wild growth predominates on most of the area.U

sually, the cemetery is not fenced in and is used by youth as a meeting place and for football games; suspicious people use it as a meeting place and as a hiding place from law and order.O

n the other hand, there are cemeteries that the local municipalities have supervised, working for their continual upkeep and taking care that the site is closed. In some of these places there is a sign announcing where the key can be found for visitors to enter.T

here are places where Jewish landsmanschaften organizations of Jews from those villages where cemeteries have remained, support the site and organize renovation and maintenance work. Most of the gravestones to be found today in cemeteries are made of Polish sandstone.The marble or granite gravestones were "taken" from the site. Whole gravestones and sections of valuable stone have been uprooted and taken out of the regular sandstone gravestones. The situation is different in the cemeteries of the large cities where at least in the center and the front sections of the cemetery, some of the elaborate gravestones made of expensive stone have remained.T

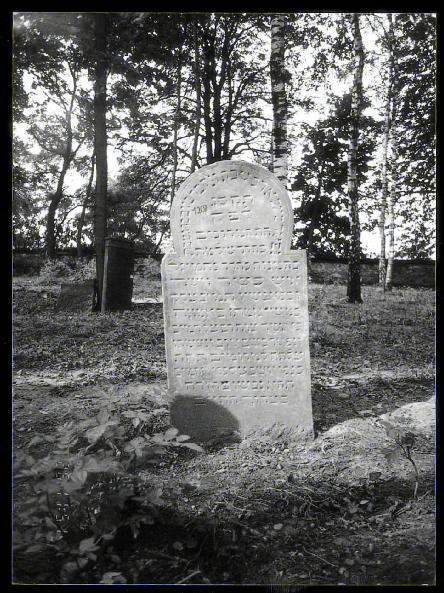

he gravestones that have remained upright are generally covered with soot and dirt, wild growth and fungus. But with the help of water and cleaning detergent, a towel, brush and much patience, it is possible to clean them and to decipher what is inscribed on them. Rubbing chalk (used on blackboards at school) on the surface of the gravestone makes it easier to read them. Gravestones that have toppled over or sunk in and are covered with layers of leaves can be read after they are raised upright and cleaned of the debris.I

n the case of painted gravestones, the paint has usually peeled and disappeared, but there are places where the paint remains until today, and especially noteworthy is the case of gravestones more than one hundred years old, whose letters are painted in gold and continue to add glamor and beauty to our memories of the past.A

s the proverb states: "The Future is Bound Up in the Past."I

n the upright tombstones of the cemeteries in Poland (as at other places) it is possible to find a strong basis for pride in our nation's past and reinforcement of the attachment to our roots.The graveyards are almost the only tangible remains of past generations, after the destruction of Jewish communities by the Nazis. They are a source of positive adthe Diaspora, self-image is not always the best since "Zionist" educationthe Diaspora.W

hat is written on the gravestones, in prose and in poetry, expresses a rich linguistic heritage of he Hebrew language and of Jewish culture. In the words of the lament, in the rich graphic design, both beautiful and fruitful, we learn of another image, lovely and full of culture of the Diaspora Jew of past generations.T

o the visitors to the cemeteries is given the opportunity to honor previous generations, generations that lived there for hundreds of years, most of whose offspring were destroyed in the Holocaust; and there is no one left to visit the graves, as was customary according to the ancient Jewish tradition, of going up to the graves of the forefathers.

The Construction of the Gravestones

O

ver the hundreds of years that Jews were buried in Europe, much thought was devoted to the construction of the gravestones, to their form, and to what was inscribed on them. Development and changes occurred both in form and approach, according to the spirit of the times. What was inscribed and what appeared on the gravestones is a primary tool for the recognition of who is buried beneath, his lifestyle and his main activities. A proper understanding of the inscriptions on the gravestones is important to the recognition the deceased and his period. There is importance in the completion of the work of the documentation as well.M

ost of the gravestones consist of a rectangular stone, set upright on the base of the grave, built of cement or bricks, with the exception of large cities where the gravestones are often of local stone.G

enerally, the upper portion of the gravestone is rounded and sometimes it is carved.T

here are gravestones with the addition of two horns at the top of the gravestone, whose significance is the forgiveness of sins of the deceased. The source of this custom is in the Holy Temple, where the Priest would spread the blood of the sacrificial animal on the horns of the altar.A

n additional source is related to the horns of the altar in the Book of Kings that tells of Adoniyahu ben Hagit, the son of David, who wanted to wrest the Kingdom for himself. After King Solomon was crowned instead, Adoniyahu went to "hold onto the horns of the altar" (Kings I, 1:50), in order to save himself from the vengeance of Solomon. From here it is commonly believed that a man who sins holds onto the horns of the altar to be saved from punishment.M

ore modern gravestones rise up high and are shaped like stairs ending in a triangle. On most of these gravestones, the text appears in Polish as well as Hebrew and in the years until the end of World War I, also in German.T

he rare forms of gravestones to be found in cemeteries in Poland are the sarcophagus or the "Tent" shrines, used as a house form over the graves of the righteous and the Rabbinic leaders of the different Hassidic groups. In recent years the Hassidic courts are renovating them.T

here are semi-round gravestones strewn on the ground and there are those upright in the form of a tree trunk or with rounded pillars. It is known that in the past there were gravestones made of wood, but they were worn away by time and the elements. In isolated places there are cast iron grave markers (in Krzepice we found many such).

The Inscription - What is Recorded on the Gravestones

A

s mentioned, the inscriptions appearing on the gravestones are of great importance in finding out information about the person buried there. The inscriptions usually are in Hebrew but there is also Polish and German, especially in the big cities.I

n the 19th century gravestones, the inscription is incised, cut-in, while in those gravestones more ancient from the 18th century, the inscription is raised and cut-out.A

t the top of the inscription, following the letters Peh and Nun (Hebrew initials for "Here lies buried") appears the first name of the deceased in large letters. Usually there is more than one given name. It is customary to add an additional name for a person who is sick, either the name of a righteous person or such as "Khai" (Hebrew for living).M

ost of the first names are Biblical, written in conventional Hebrew. But there are sometimes added to them the name in the Yiddish form, such as Leibush for Yehuda, and these are written as customary in Yiddish (in the Hebrew alphabet), with the addition of the letters Aleph, Ayin, Vov, etc., instead of vowels.I

n recent years, under the influence of assimilation, it is possible to find names in foreign languages.A

fter the name of the deceased appears the first name of the father in smaller letters. The identification of a person by calling him by the name of his or her father is very common, and we find this until today, such as when a person is called up to the Torah in the synagogue.T

he family names or surnames are written in Hebrew letters, with the addition of Aleph-Ayin-Vov according to the Yiddish rules of spelling, instead of the Hebrew form. The same goes for those names whose source is Yiddish. The name of her husband generally appears alongside the name of a married woman. Sometimes her maiden name is listed as well.A

ccording to the State Law of March 27, 1821, it is obligatory for every Jew (including the widow of a Jew) to take a family name and it is obligatory for the entire family to use this name. The limitations of the law are: it is forbidden to take on a family name using the personal name of the father and forbidden also are names identical to that of Polish-Christian families.

T

he birthplace of the deceased may also be found on the headstone. In many places it is possible to find a genealogy or delineation of the deceased's profession, such as: Dayan (Judge), Merchant, Teacher, Meyaledet, etc. Also mentioned is the family heritage (Yichus), such as: Cohen (Priest), Levite, son of a Zaddik (Righteous Person), Daughter of a Gaon (Learned Man), etc.T

he date of death/burial (day, month and year) is written after the letters Peh Nun or Peh Tet, or on the lower part of the gravestone. Hebrew letters all have a numerical value. The number of years in Hebrew letters is in an abridged form (leprat katan), without the thousands. Along the bottom of the gravestone appear the letters Tav, Nun, Tzadi, Bet, Heh (Hebrew initials for "May his or her Soul be tied up in the Bundle of Life").I

n an appendix to this booklet may be found a comparative table of Hebrew and General Calendar Years.I

n the upper portion of the gravestone, and along the upper arch, generally appears a symbol, such as a candlestick or candles that mark a woman's grave or books that symbolize a man or one of the many other symbols whose source is in Jewish culture and the Bible.Eulogy

I

n addition to the above data on the deceased, there is usually a eulogy on his or her life and activities. This is written in a lovely language, sometimes in rhymed verse, including praises on the life of the deceased, to which are added the counsel that good deeds in this world lead to a positive decree on the Day of Judgement in the World to Come.Symbols and Graphic Work on the Gravestones

I

n addition to the inscriptions, to many of the gravestones are added various incised symbols and pictures, sometimes depicting, better than in any written words, the deceased. By recognizing the lifestyle of the traditional Jew, or human culture, it is possible to decipher the significance of these pictures.A

ccording to tradition, the creation of the figure of God, an idol or a human being is forbidden in Jewish plastic arts. These limitations are well-preserved in the graphic production at the Jewish cemeteries. Following are some widespread examples of pictures and various engravings, and their significance.The Human Figure

T

he figure of a human or an idol are absolutely forbidden according to Jewish law but human hands do appear on thgravestones. The blessing of the palms of the hand are a symbol of belonging to the Priestly caste (Cohen). A hand holding a pitcher or bowl indicates that the deceafrom thLevittribe, whose function in the Temple was to wash the hands of the Priest, a custom still kept today, when the Levite in the synagogue serves the Rabbi before the Priestly Blessing on the three festivals, Passover, the Festival of Shvuoth, and the Festival of Tabernacles.

O

ne may also see a hand tossing a coin into a charity box on the gravestones, or holding a feather, or an inkwell, indicating that the deceased was a scribe who wrote Torah scrolls.Animals and Birds

T

he lion, King of the Animals, symbolizes strength and power. We sometimes see the lion standing guard, protecting and supporting other symbols, especially crowns or pillars of arches. The lion is the depiction of the Tribe of Judah and also serves to indicate that the deceased's personal name was Aryeh, Judah or Leib. Similarly, when a deer appears on the gravestones, it indicates that the personal name of the deceased was: Zvi, Hirsch or Naftali, and a bear on a gravestone indicates the names of Dov and Ber.

T

he bird sometimes represents the deceased whose personal name was Tzipora, Yonah, or Feige, etc. Birds appears on the gravestones of many women. The most prominent bird image is of a bird spreading its wings and feeding its goslings, that appear on the gravestones of young mothers who left behind small children.

T

he eagle, King of the Birds, is a symbol of strength and power, and parallel in the depiction of a woman to a lion.T

he snake symbolizes the belief in Eternal Life and the Coming of the Messiah.S

heep represent love for a departed one and pain on his or her death.Plants and Trees

I

n Jewish cemeteries, alongside elaborate geometric designs are gravestones with foliage and trees. The tree on a gravestone symbolizes Life and the creation of the world renewed. A broken tree or branch is a sign that the deceased was young at the time of death. Most of the trees are ones mentioned in the Bible: the olive tree, the grape vine and the fig tree in later periods. The Tree of Life represents a definition of the Creation of the World. The Torah is compared to a tree. In later generations, under foreign influence, round laurel wreaths of victory may be found.Candlesticks and Candles

|

The candle is one of the most accepted symbols of the woman, indicating her obligations in religion. The candle was lit by the Jewish woman and illuminated the home. Most of the candlesticks have three branches but there are ones with two, five and more. A broken candle or broken tree on a gravestone symbolizes an early death, at a young age. |

|

Books

T

he book is the main symbol of the Jewish people and the most widespread symbol on the gravestones of men. The book indicates that the deceased was a studious person or sometimes a scribe.S

ingle books may be seen or groups of books, sometimes arranged in an open bookcase, or on shelves.A book on which is written "Psalms" tells of someone diligent in the reading of Psalms, who belonged to the "Tehilim Zugeres" Society, a group who would rise early on a daily basis, summer and winter, to read the Psalms together, before the morning Shakharit service and the beginning of their workday.

B

ooks sometimes appear with the words "Tzena U'Re'ena," indicating a learned woman.

|

|

"El Male Rahamim" [G-d full of Mercy] is a prayer said for the memory of the deceased. It appears in part or in full on gravestones, sometimes covering the whole tablet of the back of the gravestone. |

Star of David

T

he Star of David was a folk decoration at the birth of our Nation and used as such also by Christians and Moslems. Only in the 17th century was it considered as a Jewish Messianic symbol and used as a symbolic decoration similarly to the way the symbol of the Cross was used by Christians.I

n the 19th century, the Star of David began to appear on synagogues and Jewish communal buildings. In 1897, the first Zionist Congress in Basel chose the Star of David as the symbol of the Zionist movement.D

uring the Holocaust, the Nazis marked the Jews with a yellow cloth Star of David badge or a white ribbon on the right arm for identification and as a mark of shame.T

oday, the Star of David appears at the center of the Flag of the State of Israel. The Star of David when found on many gravestones from the last century indicates that the deceased was a Zionist and active in the national revival movement - Zionism.Symbols

S

ymbols of various organizations sometimes appear on the gravestones, for example, at Tomashow Mazowiecki, the emblem of the Bund movement and at Zeviaritza the emblem of the right-wing Poalei Zion movement.Crowns

|

On the gravestones appear three crowns: In addition to the above Mishnah that compares a good name with oil, the tractate Avot deRabi Nathan expands, and says that there are four crowns. Some attribute this latter tractate to be a continuation of the Mishnaic tractate Avot. |

|

Biblical Pictures

|

|

On the gravestone of the deceased Rachel one can find a picture of a well, signifying the meeting of Rachel with Eliezer the servant of Abraham near a well (Szydlowiec Cemetery). All these pictures include important elements in the recognition of the deceased and, moreover, of the lifestyle of various communities, and the important highlights of their lives. |

The Influence of the Surroundings

F

rom the end of the 19th century, the cultural influence of the environment makes its impact on the Jewish cemeteries, in the design of the gravestones and the decorations upon them, such as flower wreaths or laurel wreaths. There also appear often, especially in the big cities, names in Polish, German or Russian. The year of death is often written according to the Christian year.

Talking Stones

O

n most of the grave markers one may find great cultural wealth, splendor and works of art. The painting and sculpture on the gravestones complete the words of eulogy. The depictions and the symbols widely prevalent repeat themselves and are drawn from the Jewish heritage.A

long with this are sometimes found influences from the surrounding culture (victory wreaths, arch forms, etc.)A

lthough the forms and symbols repeat themselves, there is no one cemetery with two identical gravestones.T

he designers of the gravestones in the last century would inscribe their names on the gravestones, as artists customarily sign their works for commercial advertisement.O

ften, the drawing and sculpting on the gravestones express pain and mourning of those left behind following the death of the loved ones.Dangers and Helpful Tools Necessary to Work at the Cemeteries

T

here are lurking dangers for the worker at the cemetery: holes and cesspools, hidden in the foliage, and the danger of falling into them. One must be careful to avoid leaning on branches and trees, since some of them are dry and rotten. When approaching a gravestone, it is imperative to exhibit caution and to check whether it is stable, it sometimes happens that a light touch may cause the tombstone to topple over.T

he tools needed to work in the cemeteries are: a trowel, an ax, and iron pipes or tree trunks to push up fallen or sunken gravestones. Very important are work tools for cutting wild foliage, tree roots and bushes. In order to open up an approach to the gravestones, it is imperative to use these tools as well as the hands of trained gardeners.I

n order to document the gravestones it is necessary to prepare in advance: writing utensils, drawing paper and a special permanent marker that does not fade in water.I

t is necessary to be equipped with white chalk (such as used for school blackboards). Chis of very great help in identifying whais inscribed the gra. One rubs a layer of chalk on the gravestone inscription and the upper part, covered in white, while the rest remains black, allowing for an easy rendering of the text for reading.I

t is vital to have in advance plans of the cemetery and to draw up a map. This includes the and breadth of the cemetery, or if these are not available, the cemetery is divided according to sections and the numbering of the gravestones within each section.T

he documentation of the gravestones should be undertaken according to a pre-prepared plan, to mark the gravestones, and one should place a sign allowing future visitors to find the desired gravestones.T

here is no guarantee that the cemeteries will remain for a long time, their future existence is in doubt. It seems to us that the most worthwhile and practical manner to preserve them and to pass on their historical, cultural and moral values for the coming generations is in the documentation and distribution of the documented material in print and on the Internet.T

he human factor of the local population must be taken into account according to the rule: "Honor them and suspect them." It is not recommended to engage in discussions with negative elements, most of who come from weak populations, marginal youth, drunkards, etc.I

t is sometimes possible to gain the assistance of the local populace ready to lend a hand and among them: government representatives, intellectuals, historians and researchers. There are those who are aware of and acknowledge the contribution of the Jewish people to the culture and market economy of Poland.I

have met with local residents ready to assist. They repeatedly said that, today, in Poland, it is not possible to learn the history of Poland without knowing the history of the Jews, and in order to appreciate the culture of Poland it is necessary to study the great contribution of the Jews to this subject.T

he cemetery or House of the Living as it has been called since the scholars of the Talmud said, "the righteous in their death are called the living," and it says [in the Bible] "and your nation is entirely of the righteous." The photography and living record of the communities destroyed in the Holocaust may be drawn from the Houses of the Living that remain.A

ccording to Jewish law, it is customary to visit the graves of our forefathers and relatives. This too has been denied the communities destroyed by the Nazis in the Holocaust. In the documentation of the cemeteries, it is perhaps possible to repair a bit the decree and to bridge the gap between the generations!C

ongratulations and many thanks to all those who have worked on the documentation of the cemeteries.It has been a pleasure for me, and I was glad to be of assistance,

Sincerely,

Benjamin Yaari

6 Hadror St.

Holon 58801

Tel. +972 (0) 3 5505432

![]()

Back to Yaari & Ada Cemeteries Project Web Page

SHALOM !

Last updated April 18th, 2003