Shoshana Margulis Kohn was born May 10, 1913 (3 Iyyar 5673) in Zakroczym, Poland and passed away July 1, 1996 (14 Tammuz 5756) in Jerusalem, Israel. She is buried in Kfar-Malal.

We Remember Jewish Zakroczym!

Shoshana Margulis Kohn - Memories

Transcription of a recorded interview from 1992, done by Drora and Tal Alon

Edited by Nir Alon

This material is owned by Nir Alon and may not be copied or distributed without written consent.

***

Shoshana Margulis Kohn was born May 10, 1913 (3 Iyyar 5673) in Zakroczym, Poland and passed away July 1, 1996 (14 Tammuz 5756) in Jerusalem, Israel. She is buried in Kfar-Malal.

M

y grandfather on my mother's side, Avraham Eliyahu Levkovitz, known as Abrum-Elya, and my grandmother Rachel, were from Plonsk. My mother Sarah, known as Surtze, was also born in Plonsk. My father, Itzchak-Leib Margulis, was from Zakroczym, a small town not far from Plonsk. My mother had a sister named Sheindle and a brother Moishe. Moishe deserted from the Polish Army in WW-I and went to Belgium. He was not allowed to return to Poland. My father had a brother in Plonsk named Pinchas. Pinchas's wife passed away and left him with three unmarried daughters. Pini had a lot of money from a delicatessen he owned in Plonsk. My father had another brother who lived in America. I don't remember his name.I

t is very sad for me to remember the stories of my parents wedding, and the happy life they lived together in Zakroczym ... until Hitler.M

y parents' engagement took place a whole year before their marriage. During this year they barely met except for once a month in the presence of my mother's sister Sheindle. Throughout this year preparations for the wedding took place including sewing new clothes for the bride and groom. The wedding was an eight-day festival including the Seven Blessings and feasts.Z

akroczym was a very nice small town. Zakroczym sat on a hill above the Vistula River surrounded by forests. At the top of the hill on a cliff sat an ancient castle that once belonged to princes who governed the area. The Jews in the town were very lively and our lives were rich in content. There were cultural activities, two synagogues, a mikve and all other necessary Jewish services. The Jews were very religious and observant of Mitzvot. The boys would sing in the synagogue choir under the instruction of Fater, the Chazan-Shochet.F

ater was a very nice man with a beard and had three children, one of them a mute daughter. Later, in Israel, I learned from his daughter Freida, of their escape over the Polish border at night at the outbreak of WW-II. Fater's wife, weary of reoccurrence of previously experienced progroms against the Jews, decided they should try to escape. They were lead by a gentile whom they paid to take them across the border. After Freida and her brother, Issaskhar, crossed, they heard shots fired behind them. Their parents and mute sister were killed.

Issaskhar Fater (left) and his pupils from the nearby town of Dobrzyn

A

fter their wedding my parents moved to Zakroczym. My grandfather bought them their home. I was the eldest. We were seven brothers and sisters. After me Dov was born and then Chaim, and Yekutiel, who died young of pneumonia, then Esther, Bluma and Yekutiel. My parents had a flour grinding mill and a big grocery store. On Mondays and Thursdays they would buy wheat from the gentiles and grind it to flour at the mill. In the grocery store I remember we sold lots of yeast for the gentile's poultry and chunks of salt for the cows. The cows would lick the salt and provide more milk. My parents also bought a milking cow and made sour milk and cheese at home. There was a gentile who would take the cow to pasture every morning and return her at noon for milking. The store and mill were closed Saturdays and Sundays and so was our school. My father would ride to Warsaw once a week on business.M

y father's father, Efraim Margulis, lived with us at home. My grandmother died during WW-I. Every morning he would make us cocoa and buy fresh rolls from the bakery. He tried very much to help my mother. If he would see me speaking to young gentile boys at our grocery store he would always notify my father.W

e had a very big yard behind our house. Trees were gathered and sawed to building lumber. In the yard we also kept our cow, chickens and ducks. The children would also play in the large yard and I once fell over the lumber and broke my nose, which is why it is still curved today.E

very evening I would take my sisters to the Vistula River to bath. On the opposite bank lived the gentiles who were our customers at the mill and store. Their main occupation was agriculture. Sometimes we would cross the river by boat and visit their families. Because of Kashrut laws they would offer us only potatoes and sour cabbage that was a delicacy. In the winter the river would freeze and people would ride on the frozen river with horse and carriage. As children we built snowmen, skated on the ice and threw snowballs. In spring the ice would break up and huge chunks would flow down the river. The melting ice would often flood the surrounding areas and everyone from Zakroczym would come to watch.T

here was one very unfortunate family in town - an old mother, a sister and a small daughter. All three of them were very ill and bedridden. My mother would cook for them every day and sent me to bring and serve them the food. They lived about one kilometer away from us and everyday, including winters in snow and ice, I would bring them their lunch. Sometimes most of the soup spilled out on my dress on the way. At their home I would open the cupboards, take out dishes and serve them in bed. I was 9 or 10 at the time. Their little daughter was sick with cancer. Every evening my mother would go over to bath and dress her until she passed away. There was a sense of togetherness and mutual responsibility between the Jews of Zakroczym.My

brothers and I studied at a public school in Zakroczym, together with the gentiles. There was no Jewish school in town. We had excellent friendly relationships with the gentile children. I shared a bench with a gentile girlfriend. We spoke Polish between us (at home we only spoke Yiddish). We learned French as a second language at school. Later I had private lessons in German. French was very confusing for me but I did very well in German. In the fifth grade they started teaching religious studies. The priest taught the gentile children. The Jewish children left school during these lessons. Twice every week we learned Tanach in the afternoons with a Jewish teacher. I enjoyed these lessons very much and I remember all the Jewish children did too. The Tanach and the history of the Jewish people fascinated me.I

remember one day at school, Mote Felva told a joke in Yiddish. The gentile kids were very upset because they didn't understand the joke. The principal was called to the classroom and ordered Mote to translate the joke to Polish. Mote refused for some reason and he was sent to stand in the corner of the classroom under the crucified image of Jesus that hung on the wall. The principal again demanded an explanation and when Mote refused he was ordered to bow to the image of Jesus. I remember we were all frozen in fear but Mote was very brave and told the principal he would not. Mote was expelled from school.D

uring my childhood I remember a very normal life in Poland in general and specifically for the Jews. During the Pilsutzki regime there was no anti-Semitism. There was a story that he was saved by Jews when Poland was conquered and he was marked for assassination. He was hidden by Jews and wore a Talit and Tfillin. He vowed to help the Jews. There were youth movements in Zakroczym including Hashomer Hatzair, Hanoar Haoved, a communist Jewish youth movement, the Bund and later Beitar. Beitar was very militant. They didn't accept everyone into their group. They wore brown uniforms that reminded me of German Army uniforms. I had a friend named Beni who was in Beitar. I remember there were things I was afraid to talk to him about. They trained with firearms in preparation for Aliyah to Eretz Israel. There were also groups specifically for training for Aliyah. I remember even the children from rich families preparedAliyah, doing despised jobs in order to save money and prepare for Aliyah. I remember Pini Tishman, who was from a rich family, pulling carts with garbage until eventually he did make Aliyah.M

y grandfather, Abrum-Elya, during WW I, lived in America for 10 years with his son Meir Nachman. They worked as tailors in a shop and sent home money. After the war a friend of the family from Zakroczym visited them and told him that one of his sons had fallen off a cart, broken his leg and died. Until then my grandmother kept this a secret from him. They returned to Zakroczym with enough money to buy a house and a small factory with 17 sewing machines. My grandfather had many workers in the factory - all of them Jewish. They taught me to sew with a machine and every time I broke a needle they kept it a secret from my grandfather.P

reparations for Shabbat began on Thursday. We would bath in the Vistula River and shine all our shoes. Friday morning we prepared fish and fresh chala. The table was set and prepared by noon. On Shabbat we never did the dishes or any other type of work. Everything waited for Sunday.M

any Fridays we would go to the house of my grandfather Abrum-Elya and my grandmother Rachel for Shabbat. Sheindle, my mother's sister was always there too. Together we would go down to the Vistula River to bath at the Mikve. It was about 2 kilometers away. My grandmother prepared delicacies from black forest berries that everyone loved. During the Erev-Shabbat dinner we would all sing competing for the loudest singer. It was always very happy and there was plenty of food. On Saturday my father and grandfather would read from huge religious books covered with elegant leather. I have never seen such elegant books since.T

here were rich forests around Zakroczym. The gentiles built recreation homes in the forest that they would rent to rich Jews from Warsaw. Meir Nachman's wife would take their children there every year. We would take hikes in the forests on holidays. I also remember we were there once on Lag BaOmer with my youth movement group.T

here was a rumor that Valach, the mayor of Zakroczym, was a relative. He greatly helped the Jews of Zakroczym. If, for example, someone had done something against the law, Valach would invite the police chiefs to his home for a feast in order to soften their hearts. Later in Israel I saw a photo of Valach with a yellow arm band in the ghetto.A

bout a month before every Pesach my father would prepare two barrels for Matzot. He would cover them with white sheets and lock them in a room. The children were not allowed to come near them because of fear they would be contaminated with Chametz. There was a special smell of Matzot in the house weeks before Pesach. On the eve of the Seder there were three pairs of beautiful silver candleholders on the table. The children would get lots of nuts for Pesach, that were imported from Eretz Israel. On Purim everyone wore costumes including adults. You couldn't even recognize your neighbors. The whole Jewish community gathered in the synagogue for the reading of Megilat Esther. On Shavuot there was a wonderful smell of dairy products and fresh butter cake. On Sukkoth every family built a Sukka and it was a festival for the children. Yom Kippur was always punishment for me. Being the eldest it was my responsibility to care for the children of all the close families. I would prepare their meals in a gentile neighbor's house and sometimes it was very difficult because I was hungry myself. The parents would come to check on the children at noon.

Youth Movement in Zakroczym, from Shoshana Margulis Kohn photos collection

I

never visited Warsaw until I decided to study hat-making. I finished elementary school and began highschool when I got an invitation from Uncle Moishe in Brussels to work in his hat shop. We decided I would first study hat-making in Warsaw. I was 14 when I first rode with my father to the big city on a horse and carriage. We first visited a factory for straw hats in a basement of a big building but my father would not allow me to work in a basement every day. Finally we found an arrangement by which I would study with a famous Jewish hat-designer. When we first visited her she asked me to sew a hat from fur. When I was done she asked how long I had been sewing hats. When I told her this was the first time I had ever tried she immediately accepted me as her apprentice at half the normal cost. She had hats made of silk and feathers from rare birds. All Warsaw's rich population would buy their hats from her. My father took me around Warsaw and taught me how to get along in the streets of the big city. Half the city was inhabited only by Jews although they spoke Polish. The Jews in Warsaw were either very rich or very poor. After prayers a bunch of young men would take a big basket and collect food from every house and distribute it to the poor. Every Pesach they distributed Matzot to everyone in need. I slept at the home of a girlfriend named Gutcha, the daughter of Avraham Hedmeyski. At the beginning I paid rent but later helped out with chores instead. I slept with Gutcha in the same bed - there wasn't any spare room in the house. I worked every day between 08:00 - 13:00 and then had lunch at kosher students' restaurant that was very cheap. On Fridays and Shabbat I had meals in a private home that would take several families for home cooked Shabbat meals with singing and everything. I went back home to Zakroczym only on holidays but my father would visit every week while he was in Warsaw for business. He brought me clean clothes and took my laundry. I went out a few times to the theatre and learned to know Warsaw but I missed my family and my home. We had relatives in the old section of Warsaw - a cousin who was a painter and had two sons and a daughter named Helenke. They were somehow related to my grandfather Abrum-Elya. After two years in Warsaw, when I felt I had learned enough hat-making, I went back home to Zakroczym.

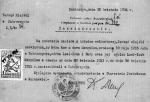

The attached document is a certificate of residence issued to Shoshana Margulis Kohn in 1934 in Zakroczym; probably in order to get emigration authorization. (Click to enlarge it).

I

nstead of going to Moishe in Belgium I began thinking of Eretz Israel. Yossef and I were matched by the wife of Rabbi Blachman, a relative of Yossef, to be fictitiously married in order to obtain immigration certificates to Palestine. Yossef saw me for the first time when I was 16. I wore two braids. He agreed. Before this meeting I had never met him or his family because I had never been to Plonsk. Beile, Yossef's mother, sent my mother a letter inviting her to Plonsk. My mother went and they closed the "deal". They would take care of the immigration certificates through Shlomo Lavi and I would pay for both our journeys. Yossef invited me to Plonsk. He took me to a hairdresser at my expense and then to a Sylvester party. I went back to Zakroczym and Yossef came to work for my grandfather in his sewing factory. After a while he went to Warsaw but couldn't find work and then he tried again in Plonsk without success. We waited a whole year for the certifictaes.B

eile, Yossef's mother, wrote to Shlomo Lavi asking him to provide with a certificate as well. She was a widow and therefor allowed immigration by herself (editor's note: only married couples could obtain immigration certificates from the British Mandate). Beile took Leah with her but was stopped at the train station because she didn't have a passport and certificate for Leah. Sheindle was already in Israel. She had made Aliyah earlier to help Shlomo Lavi with his children when his wife passed away. Shifra, David and Henya (who married Shlomo in Warsaw) were already in Palestine but their financial situation was very difficult. Later when I arrived I saw they didn't have shoes, their blankets were torn and they barely had anything to eat. Meir went to America. Shlomo Lavi brought his mother, Sarah, to Israel and she lived with Henya.T

he jouto Eretz Israel was tRomania. My mother sewed a few gold coins into my coat lining so I would not be robbed. My mother accompanied us. She told me she knew this was the last time she would see me. In my heart I hoped that one day I would come back with my children to visit their grandmother, my mother.![]()

E

ditor's note:Shoshana never got the chance to ther daughters to visit their grandmother in Zakroczym. The Nazis wiped out the entire family remaining in Zakroczym.

This material is owned by Nir Alon and may not be copied or distributed without written consent.

Nir Alon, April 2000

Last Updated January 12th 2003