In memory of Dr. John Nowik z"l who has initiated this web site and who translated Szlengel's poems straight from his bleeding heart, but didn't live to see it on-line...

We thank Sebastian Angres, Edyta Gawron, Josef Holender and Jan Jagelski for their help in this project.

Halina Birenbaum &

![]()

...These

poems-documents I was supposed to read to human beings who believed they will survive,

I was supposed to review with them this volume as a diary of a dreadful period,

which has passed to our joy, memories from the bottom of hell - but comrades to

my wanderings disappeared and the poems became in one hour the poems which I

read to the dead... Władysław Szlengel

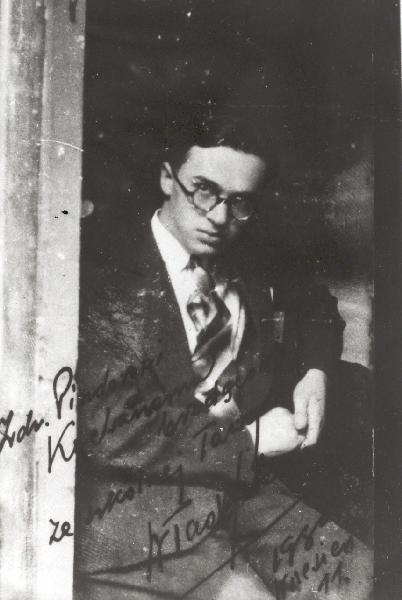

Władysław Szlengel

1914-Ghetto Warszawa 1943

The photo has the dedication of the poet to a

friend date: 11.9.1939

Web Site initiated by Halina Birenbaum and Ada Holtzman April 2003

Selected Poems I (Polish & English & Hebrew)

Selected Poems II (Polish & Hebrew)

Selected Poems III (Polish & Hebrew)

Selected Poems IV (Polish & Hebrew)

Ce

que j’ai lu aux morts…

Szlengel Poetry Translated from Polish to French by Jean-Yves Potel

![]()

What I Read to the Dead (Polish)

What I Read to the Dead (Hebrew)

What I Read to the Dead (English)

What I Read to the Dead (English - in Kobos Web Site "SHOAH")

Aftermath (Hebrew) | Note to the Pedantics (Hebrew) | To the Polish Reader (Hebrew)

An Account with God | A Talk with a Child | The Monument | Nihil Nivi |

Kobos' Web Site with Szlengel's Poems in English | Kobos' Web Site with Szlengel's Poems in Polish

|

Mała

Stacja Treblinki Na szlaku

Tłuszcz-Warszawa, I podróż trwa czasami A stacja jest maleńka I nie ma nawet kasy Nie czeka nikt na stacji I milczy słup stacyjny, I tylko wisi z dawna

|

|

|

Władysław Szlengel A Small Station Called Treblinka* On the line between Tluszcz and The journey lasts And the station is very small And not even a cashier And nobody waits for you in the station And silent are the three fir trees And only a commercial board * Translated from Polish to Hebrew by Halina Birenbaum and from Hebrew to

English by |

ולאדיסלאב

שלנגל כאן

התחנה

טרבלינקה בקו

שבין טלושץ –

ורשה מתחנת

הרכבת ורשה

אוסט יוצאים

ברכבת

ונוסעים ישר... הנסיעה

נמשכת

לפעמים חמש

שעות ועוד 45

דקות ולפעמים

נמשכת אותה

נסיעה חיים

שלמים עד

מותך... והתחנה

היא קטנטונת שלושה

אשוחים

גדלים בה וכתובת

רגילה אומרת: כאן

התחנה

טרבלינקה… כאן

התחנה

טרבלינקה... ואין

אפילו קופה גם

איש המטענים

איננו ובעבור

מיליון לא

תקבל כרטיס

חזור... ואיש

לא מחכה

בתחנה ואף

אחד לא מנפנף

שם המטפחת רק

באוויר

תלויה דממה לקדם

פניך בשממה

אטומה. ושותקים

שלושת

האשוחים שותקת

הכתובת

השחורה כי

כאן התחנה

טרבלינקה... כאן

התחנה

טרבלינקה... ורק

תלויה עוד

מאז סיסמה

ישנה ובלויה

האומרת "בשלו

בגז". |

![]()

Yankel Wiernik: A Year in Treblinka, New York 1945

![]()

|

Am I allowed to tell Szlengel? Am I allowed to tell Szlengel Endless ruins cover him Is it fair to postpone him And who will listen to the dead I have many comforts Am I allowed to be silent Halina Birenbaum 7.5.1985 |

|

![]()

Władysław Szlengel in the

Source: Jewish Historical

Institute ref 263/a,b

![]()

The first collection of Szlengel

poems was published by Michal M. Borwicz: Piesn Ujdzie Calo, Antologia

Wierszy o Zydach Pod Okupacja Niemiecka,

A comprehensive collection of

Szlengel's poetry was edited by Irena Maciejewska and was published in

Szlengel's book "What I read

to the Dead" was translated to Hebrew by Halina Birenbaum and

published by the translator in 1987.

Halina Birenbaum

dedicated the book "to all those with whom I read Szlengel poems at the

threshold of the total destruction of the Warszawa Ghetto"

Władysław Szlengel Kronikarz Tonacych - Andrzej Kobos's web Site

(Polish)

![]()

|

Władysław Szlengel Kartka z Dziennika Akcji Published in "Mosty" the

Newspaper of "HaShomer Hatzair" nr. 4(12), Published after the War |

|

|

|

|

A Page from the

Diary of the Actions

Translated by Dr. John Nowik and edited by

Today I have

seen Janusz Korczak,

as he walked with the children on their last procession

and the children wear civil and clean clothes

as though on Saturday walk going to the park

They wore clean

aprons of the holidays

but today they could dirty them

Five by five the Home of the Orphans went across

the town

through bushes of pursued people

The city had a frightened face

a mass of naked and stripped crowd

the streets were watched by empty windows

like skeletal orbits of the dead

Occasionally a

cry of a lost bird demented

a death knell rung without reason

while indifferent Messieurs rode in hand driven carts

the Messieurs masters of the situation.

Sometimes footsteps, scraping and then a silence

someone in the flight spoke in a hurry

frightened and speechless in its prayer

stood in the church on

And here the

children five by five, peacefully,

no one was pulling anyone from the rank,

these are the orphans, no one was offering bribes

into the hands of blue policemen.

There were no

interventions on the Umschlagplatz

no one whispered into the ear of Szmerling 1)

no one collected family watches

for the drunken Lithuanians

Janusz Korczak

walked with a straight head

with bare head -

by his pocket held him a little chi

and two small ones he held them in his arms.

Someone

Someone rushed exp

"you can return this a paper from Brandt"

Korczak silently shook his head refusing.

He did not even

tried to explain

to those who came with the German offers

how would one put into those soulless heads

what it means---to leave a child in such an hour all alone....

So many

years.... in this road so steep,

to give in the children's palms the sun's sp,

how would he leave the frightened one,

he would go with them... further... till the end of all the roads...

And then he

thought about King Matthew,

that the fortune has deprived him of the same fate.

That King Matthew on the island among the

wild ones

also would act the same.

The children

were went into the cattle trains

as though on a trip on "Lag Ba'omer"2)

and the little one with the look of the brave

Felt completely like "Hashomer"3).

I thought in

this so ordinary moment

for

that he for us all was writing history

the most beautiful of pages.

That in

this Jewish cursed War,

in the endless humiliation without an end,

in the helpless chaos,

in that fight for life for any price, without a compromise,

In the depth

of corruption and betrayal

on that front, where the death has no fame

in this nightmare of dancing in the night

there stood a single and a proud soldier

Janusz Korczak, the orphans' caretaker.

Do you hear

neighbors from across the wall

as you watch our deaths from the other side of the bars?

1) Szmerling:

Commander of the Jewish Police in Ghetto Warszawa

2) Lag Ba'omer - The thirty-three day of the counting of the Omer; a festival

3) Hashomer - (Watchman) Jewish self-defense organization founded in 1905. Also name for a member of Hashomer Hatzair (Socialist & Zionist

Youth Movement).

![]()

The

Word Which Never Gets Lost

Polish: " Nowiny

Kurier "

Hebrew: "What I Read to the Dead", Introduction by Halina Birenbaum1987

Translated by Edyta Gawron and

The writer Amos Oz in his excellent television program said recently that the word never gets lost, even the one uttered in the desert... I think that what I know and remember about Władysław Szlengel, one of the most popular poet in Warsaw Ghetto, only confirms this deep and extraordinary truth...

The poems of Władysław Szlengel were read in houses of the Ghetto and out of it, in the evenings and were passed on from hand to hand and passed from mouth to mouth. The poems were written in burning passion, while the events, which seemed to last for centuries occurred. They were living reflection of our feelings, thoughts, needs, pains and merciless fight for every moment of life. I recited in the Ghetto some of his poems in many meetings and small performances organized in order to collect some money for starving inhabitants of our houses, streets and for refugees expelled from their small towns, whose number was rising tragically every day. I was 12 years old by then.

Later,

when from over half a million Jews in Warsaw Ghetto remained only 30-40

thousands, in January 1943, through workers in the Shop or "Placowki"

(factories outside the Ghetto), we managed to get hold of two copies of

Szlengel's poems. With profound and bitter emotions my 20-years old

sister-in-law, Hela Grynsztejn ne'e Herszberg, read

them for us. There were "Treblinka"

and "Obrachunek z

Bogiem" (An

Account with God). In every moment Germans could rumble in their

boots on our stairs and kick in our doors and transport us to Treblinka. We expected this to

happen and it was our only reality in this world taken by Nazis's dreadfulness.

How actual and meaningful sounded than these poet's words! I memorized their

contents, atmosphere and "melody" (which was as well mine, ours), and

the images of this room at

Probably

these words soaked then into my blood with this terrible fear of undeserved

death waiting everywhere and the whole unexpressed sufferings awaiting us!... They remained inside me forever and became a part of my

identity. For the last time in the Ghetto I listened to Szlengel's poems with

part of my family (father and most of my relatives were already taken to the

Umschlagplatz in previous Actions (Akcja). The poems were recited with passion

and inner satisfaction by my younger brother Chilek (20 years old). It was

"The Contra-Attack". It was day before the outburst of the

uprising in Ghetto, a few hours before going down to the bunker at

I remember

it! I soaked it into my whole self! Those moments are inside me till now and

probably they will stay until I die... I am not certain if I have enough words

to express it; however, I feel it so clearly and sharply to the extent of pain.

My brother was reading: "On the filthy stairs of Jewish

I

survived. Nearly alone. No one of them survived. But

this is known. Later I was always telling about these poems from my

"childhood", about their fascinating content, so tragic, so full of

expression. After the war I was telling about them to my new friends, my

students and my family. I was looking for those poems but for some reasons I

haven't found any publication. I even thought that I am the only one who

remembers Szlengel... And suddenly after 40 years, I came across a book: "What

I Read To the Dead," written by

Władysław Szlengel. One woman left in her inheritance a collection of

Holocaust books to the "Massua"

institution in Kibbutz Tel Icchak. In "Massua" the intensive seminars

have been taking place for many years, for high school teenagers from

I started

checking, looking for "my" familiar poems. I found one after another

like addresses of houses in which I was living, like dear people whom I haven't

seen for years. There were there, all of them. Dizzy with emotions I started to

read my familiar, dear words, engraved in my heart! Unintentionally I started

reading it loud, straight in Hebrew in order to let people - who surrounded me

and who were surprised by my emotions, to understand what made me so excited. I

only haven't found "Obrachunek z Bogiem - An Account with God".

But at the end of book, Irena Maciejewska, the editor of the collection, wrote

that among the notes of the Ghetto historian Ringelblum, the poem

"Obrachunek z Bogiem" is mentioned, but the original version didn't

survived. Although she repeated some verses, which weresimilbtaken from the

poem "There is a time now". They were not able to solve this

problem.

These words were not found at that time, didn't get to the editor of the poet's collection of poems. I thought that the War burnt them totally. As well the poet, great in his persistence and faith in the life and in the written word, killed in a bunker during the uprising of the Ghetto Warszawa. All those people who listened to his creations, read and loved his poems were burnt, were choked by gas, were killed by guns. The odor of their burnt bodies and their last scream remained inside of me forever.

I am

evidently, in this case that

I wanted

Szlengel to live where I live, in

Today, these poems are a constant reminder' that everything did happen' and hat all the Jewish people existed once and hoped to survive, or at least leave their traces in the eternity. They lightened the dark days, inspired strength and a feeling that not everything had died, and if there are still persons who wrote as they did and their light shone despite of the cycles of siege and hell in which they were locked in. We were encouraged by Szlengel poems and even disillusioned ourselves that who knows, may be there is a magic power standing behind us and would bring the victory soon, the end to our sufferings... We hoped for a miracle, without realizing that the writing in itself, transmitting the poems in the by the murderers' kept area, and the ability in itself of writing and reading concealed the miracle and the victory.

A few months ago I read an article in "Yediot Achronot" about: "Will any literature exist in year 2000?" and "Is there any future for the poetry?"... It reminded me of Szlengel, who was writing his terrible chronicle of the days of extermination and general destruction of all human rights and concepts. In his presence, thousands of people were dying every day and he wasn't asking if it is worthy, if any literature would exist after the extermination in Treblinka and after the torture of the road to that hell... The creation is created by life; it is as breath of air and mainly in times of great suffering. It is the substitute to all what is human, when the man is thrown to hell. And it was proven in the days of the Holocaust,

Some part of his poetry he, Szlengel, hid in a double tabletop, which after nearly 20 years was found by a Pole in Jozefow (a small town near Warszawa) who was chopping this table probably for winter fuel... Well, poet's fortune and world's fortune - even in the most awful desert of death and total destruction the poems survived.

So the

word which never gets lost and works in so many different directions! My

excitement from discovering the poetry of Szlengel in the collection "What

I Read to the Dead", I described in Polish in the Israeli Polish

newspaper "Nowiny Kurier". After one year I received a letter from

Mr. Izydor Szulman from

![]()

![]()

|

|

Władysław Szlengel; the |

|

|

Władysław Szlengel; the commercial School; first row, the first

to the right. |

|

|

![]()

"Szyrim Lefnei Vemitoch Hamabul"

Poems

Before and Within the Flood

Hebrew, Ma'ariv Book

Guild 1990

Introduction by Halina Birenbaum

Wiersze sprzed i z czasu potopu

Z przedmowy do mojego hebrajskiego tomiku wierszy i tłumaczeń

Lata „potopu" w Shoah

zostawiły we mnie niezliczone wspomnienia, ale nie tylko o

okropnościach. Wyniosłam stamtąd ludzkie wartości,

miłość do ludzi, do życia, i miłość do

wierszy poznanych na krawędzi śmie; doich autorów, którzy przez swe utwory dawali nam otuchę i pomagali żyć -

pomagali iśćna śmierć z wiecznewartości ży.

Pły z największej rozpaczy,ale też głębiludzkiego

zrozumienia i włości, jakich doznaje się tylko w chwilach

ostatecznych.

Takie były wiersze Icchaka

Kacenelsona, Władysława Szlengla, Stefanii Ney (Grodzińskiej),

Poli Braun i innych, nieznanych autorów. Staram się nieustannie przekazać ich treść i

znaczenie swym bliskim oraz młodzieży, której opowiadam o tamtych czasach.

Wiersze te z mojego

dzieciństwa lat Zagłady wracają do mnie niezwykłymi

drogami, aż trudno uć, by mogło ę to dziać w

rzeczywistości. Wracają chyba po to właśnie, bym moła

przekć dalej wraz z moim wzruszeniem i tęsknotą do tych, z którymi je czytałam razem Wtedy.

Przedziwne przypadki

sprowadzają też spotkania z towarzyszami losu z tamtych dni. Nazywam

je „odkryciami archelogicznymi". Zwracają wspomnienia przebytych

doświadczeń, uwiarygodniają zdarzenia zacierane przez c- i w

tyicłównznaczenie.

Blumę Babic-Szadur i jej

się z getta i obozów,

Halinkę Czamarkę-Barman, spotkałam w Izraelu dopiero po 40

latach w szkole w Dniu Pamięci Holocaustu. Ukrywałyśmy się

razem w bunkrze na ulicy Miłej 3 w czasie powstania i likwidacji getta

warszawskiego. Szłyśmy potem dalej tą samą trasą:

Majdanek, Auschwitz, Marsz Smierci - Ravensbruck - Neustadt-Glewe...

Przypomniałyśmy teraz

razem tę całą przeszłość, także przedwojenne

piosenki i wiersze z getta, które ja akurat tłumaczyłam wtedy na hebrajski.

„Zaraziłam" do nich Blumę i Halinkę swym entuzjazmem, co

przyniosło nieoczekiwanie do znalezienia utworów „sprzed potopu" Władysława

Szlengla.

O przypadkach znalezienia innych

jego wierszy zebranych w książce „Co czytałem umarłym",

przetłumaczonej na hebrajski i opublikowanej przeze mnie w Tel Avivie

napisałam szczegółowo w przedmowie do tej książki. I nagle odnalazły się

jego następne wiersze.

Bluma i jej mąż odbyli

długą podróż po świecie. Halinka, przybrana siostra Blumy, dołączyła

się do nich. Odwiedzili, między innymi kuzyna Halinki w Brazylii.

Mosze Papelbaum, wyemigrował

z Warszawy, miasta swego urodzenia, jeszcze przed II wojną

światową. Ożenił

się w Rio De Janeiro z tubylką, założyli rodzinę. Z

czasem oddalił się niemal zupełnie od kultury, którą nasiąknął w

domu w Polsce.

Spotkanie z Blumą i

Halinką obudziło przeszłość z lat młodości,

tęsknotę. Zaczęli przypominać także piosenki

śpiewane przed wojną - polskie i żydowskie przeboje, popularną

piosenką: Dziś panna Ańdzia ma wychodne, Jadziem Panie

Zielonka!..."

Bluma zawołała w

uniesieniu: „a wiesz, że te słowa napisał Władysław

Szlengel, poeta warszawskiego getta, który zginął w czasie pw

kwietniu 1943 roku?"

Papelbaum ujął

głowę w ręce i zapłakał na dźwięk

wypowiedzianego nazwiska. Szlengel był jego przyjacielem

młodości, kolegą z ławy szkolnej jego brata, Ignaca,

zgladzonego w Shoah.

Wyjął z szafy

plik pożółkłych gazet i zdięć, dał je Blumie. Zdięcia

swego brata ze Szlenglem w przedwojennej Warszawie, z letniska w Otwocku;

gazety z lat 1937 - 1939 ( Nasz Przegląd, Szpilki), gdzie

publikowano wiersze, satyry i humorestki Szlengla. Przechowywał je w

ciągu dziesiątek lat, choć jego brazylijskiej rodzinie one

były obce. Teraz te przedwojenne wiersze z pożółkłych, rozpadających

się niemal gazet przemówiły nagle, jak proroctwo. Własne doświadczenia i czas

dokazały tego na jakże bolesnych faktach!

Bluma przywiozła mi te

gazety i zdięcia - skarb z Brazylii: powinnaś je

przetłumaczyć, by nie zginęły, by te wiersze poznano w

Izraelu! Nie musiała mi o tym napominać. Było to moim

wewnętrznym poczuciem obowiązku, celem.

Część

wierszy Szlengla odnalazło się w archiwum Emanuela Ringelbluma pod

gruzami getta. Kilka wierszy znalazł pewien Polak z Józefowa, gdy rozrąbał stół przyniesiony z getta - niektóre wiersze ludzie odtworzyli z

pamięci.

Tak też z wierszami

Poli Braun i Stefanii Ney, które występowały razem ze Szlenglem w getcie w kawiarni „Sztuka".

Steafania Ney i Pola Braun występowały również jako śpiewaczki i

recytatorki w getcie warszawskim w teatrze Femina.

Pola Braun pisała

teksty i komponowała muzykę do swych piosenek, śpiewała je

też więźniarkom na konspiracyjnych spotkaniach w obozie na

Majdanku. Polę Braun rozstrzelano wraz z 18.500 Zydami w środę,

3 listopada 1943 roku. Miała dwudzieściekilka lat.

Wiersze Szlengla, Ney i

Braun opublikowano po wojnie w antologii „Pieśń ujdzie

cało". Komitet żydowski zorganizowany jeszcze w czasie wojny,

wydał tę antologię w roku 1947 pod redakcją pisarza i poety

Michała Borwicza.

Kilka wierszy Szlengla w

gazetach warszawskich sprzed wojny odnalazła w archiwum uniwersytetu w

Jerozolimie i przekazała mi badaczka literatury z Tel Avivu, Ruth

Szejnfeld. Mnie się udało odnaleźć zapamiętany z getta

Obrachunek z Bogiem przez artykuł, który opublikowałam o tym wierszu

w gazecie polskiej w Izraelu, Nowiny i Kurier.

Wiersze Płyną

okręty i Szukam człowieka przyniosła mi Fira Slańska z

Jerozolimy. Zdążyła przepisać je z gazety Nasz

przegląd jeszcze w 1939 roku, na krótko przed swoim przyjazdem do

Palestyny, przed wybuchem wojny. Fira skontaktowała się ze mną

po przeczytaniu mojej książki Nadzieja umiera ostatnia,

odtąd zaczęła się i trwa do dziś nasza

przyjaźń.

Halina Migdan z Aschkelonu

zwróciła

się do mnie po przeczytaniu hebrajskiej wersji mojego tłumaczenia Co

czytałem umarłym. Opowiedziała mi, że przed wydostaniem

się na „aryjską" stronę na początku akcji wysyłki

Zydów na stracenie

do Treblinki pewien mężczyzna podał jej rękopisy

pięciu wierszy, błagając, żeby je wzięła z

sobą i przekazała światu, jeśli przeżyje.

Halina nie wiedziała

nic o Szlenglu, ani kim był ten, który przekazał jej jego

rękopisy. Przechowywała je przez całe życie wraz z

najważniejszymi dokumentami.

Spotkanie z Haliną

Migdan jest jednym z dowodów, że w getcie liczyły się nie mniej dzieła kultury

od własnego życia - narażano życie dla ich ocalenia i

przekazu..

Pisane w gettach i obozach

wiersze były wyrazem życia i cierpień, największym

pragnieniem pozostawienia ich śladów, zachowania

człowieczeństwa w piekle - , pomagały tam żyć i umierać.

One mogą nam opowiedzieć dziś wiernie, co myśleli i czuli

ludzie w latach „potopu" w Shoah.

![]()

Historia Odnalezionego Wiersza

(z moich

pamiętników: Każdy odzyskany dzień)

27.01.85

Gdybym była wierząca,

musiałabym powiedzieć chyba, iż jest w tym ręka Boża.

Jednak w cuda wierzę, chociaż sprawiają je lud, a raczej dobro

istniejące w nich w głębiach duszy, dobro, które na różne sposoby zostaje pobudzane poprzez

rozmaite ucznki, pozytywne działania.

Władysław Szlengel,

niezmiernie popularny poeta warszawski, napisał jeden ze swych

krążących po osierociałym getcie, czekającym

wiosną 1943 roku na ostateczną zagładę, wiersz Obrachunek

z Bogiem. Czytało się wtedy te wiersze, podawane w odpisach z

rąk do rąk, z niewypowiedzianą, głodną

zachłannością, jak wchłania się soki ożywcze,

żeby nie skonać.Widziało się w samym ich istnieniu, w

chęci możliwości tworzenia w takich chwilach - siłę

życia i jego nie ocenioną wartość. Poprzez wiersze poety o

tak aktualnej, trafnie określonej treści czuło się

niezbicie, że potęga życia ludzkiego silniejsza jest od

śmierci, Niemców,

Hitlera!

Część utwrów Szlengla odnalazła się po

wojnie pod gruzami getta warszawskiego wraz z archiwum historyka E. Ringelbluma

i została opublikowana w Warszawie w tomiku Co czytałem

umarłym.

W wyjaśnieniach na

końcu tej książki podano, że w notatkach Ringenbluma jest

mowa o wierszu „Obrachunek z Bogiem", ale go nie odnaleziono. Istnieje

tylko pewna strofka, która

treść taką przypomina, ale może to również być część innego

utworu poety. Szlengel, jak wiadomo, zginął w bunkrze podczas

powstania w getcie warszawskim i nawet wiek jego nie był dokładnie

znany.

Po przeczytaniu Co

czytałem umarłym napisałam i opublikowałam w „Nowinach

Kurierze" artykuł: Słowo, które nie ginie nigdy, gdzie opisałam obszernie, w jakich

okolicznościach zapoznałam się z wierszami Szlengla. W owej

niewiadomej strofce natychmiast rozpoznałam „Obrachunek z Bogiem" i

przytoczyłam kilka zdań utworu, które szczególnie wryły mi się w pamięć.

Kilku ców po otego zwróciło się do mnie. Nawiązałaz

nimi kontak, a potem i przyjźń, gdyż okazło się,

że wiele mze sobą wólnego,co nas serdecznie łęczy.

Wzeszłym tygodniu, po

upływie przeszło roku od tej publikacji otrzymałam list z Hajfy,

od p. Izydora Szulmana, który doniósł mi, że po

przeczytaniu mego artykułu w „Nowiny" przypomniał sobie, iż

zazaz po wojnie znajomy wręczył mu otrzymany od kogoś z Warszawy

odpis ręczny: Obrachunek z Bogiem. Dopiero teraz udało mu

się wygrzebać go w swych papierach i jeśli jestem jeszcze,

zainteresowana, chętnie mi prześle kopię...

Pan Szulman jest także

warszawianinem, przeżył wojnę wraz żoną i córką w Rosji. Oczywiście,

ście natychmizatelefonowałam. Otrzymałam z jego rąk calutki

wiersz! Miałam niespełna trzynaście lat, gdy w domu na Nowolipiu

30, w bloku Szulca przeczytano mi go po raz pierwszy, na krótko przed rozpoczęciem powstania w

getcie. Przeżyłam, zapamiętałam tak nam wtedy bliskie

treści. Jestem wdzięczna losowi za możliwość

wzięcia udziału w wydaniu na światło, w czterdzieści

dwa lata po jego napisaniu. Jednak w cuda wierzę.

A więc istnieją cuda i

dobrzy ludzie, dzięki którym dotarło jeszcze jedno Wołanie w nocy

Władysława Szlengla.

A może Bóg zawstydził się i nie

chcąc pozostawić „karty" poety - czystej, pomógł w tym odnalezieniu, aby na czystej

karcie obrachunku dopiasano jakiś czyn...

Z odnalezionego obecnie wiersza

dowiadujemy się, że poeta w chśmmiał 32 lata.

![]()

Halina Birenbaum:

The

Newly Found Poem of Władysław Szlengel

"Nowiny Kurier" (Friday, Feb.22, 1985)

Translated by Edyta Gawron

Władysław Szlengel, a very popular poet from Warsaw entitled one of his poems, that was circulating in the orphaned ghetto, expecting in spring 1943 the final extermination - ”An Account With God”.

Part of the Szlengel’s poetry was found after the war under the ruins of the

ghetto of

„After I had read “What I Was Reading to Dead” I wrote and published in the „Nowiny” newspaper an article called ”A Word that Never Dies” (21.10.83), where I described the circumstances in which I got acquainted with the Szlengel’s poems. In this stanza I immediately recognized „An Account with God” and I quoted several sentences of the poem, which particularly were engraved in my memory” - wrote Halina Birenbaum in the letter to the editor.

„After more than a year I received a letter from

Mr. Szulman is from

With emotions that are hard to describe I took the poem out of his hands. I am grateful to the Fate for this great honor of taking an accidental part in retrieving the poem, 42 years after it had been written.

If I were religious I would probably have to say there was a God’s hand in it. However I believe in miracles, though these are just people who make them, or rather the goodness that they carry in.” - writes to us Mrs. Halina Birenbaum.

Out the found poem we have learned that the poet wrote the verses when he was 32 years old, which was in the years 1942-1943.

The editorial staff of "Nowiny Kurier” wish to thank Mrs. Halina Birenbaum and Mr. I. Szulman for making available the publication the newly found poem of Władysław Szlengel.

![]()

|

Wołanie w

nocy Wiersze lipiec -

wrzesień 1942 Wiersze te, napisane

między jednym A drugim Wstrząsem, w dniach konania Wołanie... w nocy... |

A Cry in the

Night Translated by John Nowik and These poems were written between the first My cry... in the night... |

![]()

Władysław Szlengel - The Ghetto Poet, Alive,

Dying, Fighting

By Natan Gross

Translated from Hebrew by

Władysław Szlengel was born at Warszawa in 1914. His father - a painter who made a living from painting boards and announcements for the cinema. He sent his son to school of Commerce but Władysław, who helped his father in his work' discovered already in school his talent for rhyming and he found, very quickly, a way to reach newspapers and weeklies, and another path he took was his access to theaters and "Review Theaters.

At the same time Szlengel published poems and satirical prose in the satirical newspaper "Szpilki", "Pins", but also in the Jewish newspaper "Nasz Przegląd" ("Our Review") he published gloomy prophetic poems which foreboded the approaching storm - the Hitlerian danger which threats the whole human kind. Also these poems tended to a publicist style - and they clearly send their message, without metaphors or literary ornaments, see his pessimist poems like "Don't Buy the New Year Calendar" or "A Frightened Generation".

The separation from the Polish environment was very painful to Szlengel. We learn about it from his poems full of nostalgia to Warszawa. In one of them, "The Telephone", he tells how while sitting near the telephone, he wanted to speak to one of his Polish friends behind the wall of the Ghetto. To his amazement, he found out that he has nobody to call, as their ways were completely separated during the Ghetto times. This poem was probably among the first ones he wrote after the erection of the Ghetto.

The next poems are rather a chronicle of the Ghetto life

and its future. His poetry was written to the literary crowd, which had

gathered in "Sztuka" (art) coffee-shop on

The poems were not written only to the actual crowd of the "living diary", or lovers of his poetry, recited in many parties and special evenings in private homes, Szlengel was aware of the fact that he was writing for history and also to the future reader. For this reason he assembled his poems in files which he distributed in various hiding place in the Ghetto and outside the Ghetto.

To mark the 35th anniversary of Ghetto Warszawa's uprising, Irena Maciejewska published all the poems, which she managed to find - excepone: " The key at the Concierge ". This is an ironic poem, aimed at all those whowere the first to tathe opportunitgiven to them by the Germans, to rob the Jewish property and also the first to serve the new Masters. This poem was not included in the collection published in Warszawa, but we learn that Szlengel himself refrained from including it in his collection. And thus he wrote to the "pedants" who would come one day and publish his poetry: "I didn't include my poem "The key at the Concierge" because I wait with publication of this drastic subject (the title should not be taken as simple as it sounds) to days when the nationalist instincts which were inflamed by the brown shirts will fade, and with peace we will make the account with the sins of our neighbors." The poem was published in the anthology of Michal Borwicz ("Piesn ujdzie calo" - The song will sourvive, 1947) and also in the anthology of the satirical Polish poetry of Leon Pasternak and Jan Spiwak (1950).

Szlengel does not explicitly to these subjects. There is no exact key to the chronology of Szlengel's poems. But we can assume according to the contents of the poem, when they were written. So is the poem "Things", which is a rather living history of the deportations and decreasing the Ghetto's space, or "A Page from the Diary of the Actions" which describes the heroic expel of Janusz Korczak and his orphan children to the Umschlagplatz - a rare document of an eye-witness - and "Kontratak", (Counterattack) a giant testimony page to the Jewish armed uprising on 19 April 1943.

Władysław Szlengel lived all the Ghetto period

and he perished during the Warszawa Ghetto uprising in April, in the bunker of

Szymon Kac on

Szlengel erected a memorial to the simple man and he left a very unique description of the Jewish revolt. He writes under all circumstances and see himself as the diarist in a sinking ship, the poet of the dying and the murdered. His opening lines to the collection of his poems - "What I Read to the Dead" is so shocking and explain the situation of the Ghetto's prisoners,in such truthfulness that compared to it, thousand of papers written about the subject since then become pale.

![]()

Names...

Ziuta... Asia... Eli... Fanja... Siuma...

Do they tell

you anything? Nothing.

People... unnecessary people. They were thousands of them. In

thousands they were driven to the Umschlagplatz, in thousands they were bitten

by the whip, torn apart from their families, loaded into the cargo trucks,

poisoned by gas. Not important. The Statistics will not mark them

, they will not be given any

commendation.

Names. Empty sounds. For me they

were living people, relatives, tangible, these are human lives whom I have known from events in which I participated. These

tragedies intensified by feelings are more important for me than the fate of

They are gone...

As a farewell, the S.S. officer shoots at the group who was

realeased.

Władysław

Szlengel

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

Władysław

Szlengel: Selected Poems

Translated and Edited

by Halina Birenbaum

& Ada Holtzman

(Spis treści - partial list)

![]() Co czytałem umarłym – What

I Read to the Dead (Polish) Hebrew אשר

קראתי למתים

Co czytałem umarłym – What

I Read to the Dead (Polish) Hebrew אשר

קראתי למתים

Posłowie Epilogue (Hebrew) | Notatka dla pedantów Note to the Pedants (Hebrew) | Do polskiego czytelnika To the Polish Reader (Hebrew)

![]() Szałasy

(Nasz Przeglad - (Our Review) 20.09.1937) - Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacle) –סוכות

Szałasy

(Nasz Przeglad - (Our Review) 20.09.1937) - Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacle) –סוכות

![]() Wiosna

na ulicy Pawiej (18.04. 1937) - Spring on the Pawia

Street – אביב ברח'

פאביה

Wiosna

na ulicy Pawiej (18.04. 1937) - Spring on the Pawia

Street – אביב ברח'

פאביה

![]() Samolot (6.04.1937) - An Aeroplane - אוירון

Samolot (6.04.1937) - An Aeroplane - אוירון

![]() Sklepiki (18.12.1938) - Small Shops – קטנות חנויות

Sklepiki (18.12.1938) - Small Shops – קטנות חנויות

![]() Szukam cłowieka (1938) - I'm looking

for a Human Beinמחפש

בן אדם

Szukam cłowieka (1938) - I'm looking

for a Human Beinמחפש

בן אדם

![]() Przerażone pokolenie (25.01. 1939) -

Frightened Genaration דור

מבוהל

Przerażone pokolenie (25.01. 1939) -

Frightened Genaration דור

מבוהל

![]() Prima Aprilis (1939) - "Nasz

Przeglad" (Our Review) - 1st Aprilראשון

באפריל

Prima Aprilis (1939) - "Nasz

Przeglad" (Our Review) - 1st Aprilראשון

באפריל

![]() Niemowlę ( 1.01.1939) - An Infant -

1939 תינוק

Niemowlę ( 1.01.1939) - An Infant -

1939 תינוק

![]() Kol Nidrei (14.09.1937כל נדרי- (

Kol Nidrei (14.09.1937כל נדרי- (

![]() Cisza (Akwarela letnia) (13.08.1939) -

Silence (Summer Aquarelle)

שקט - (אקוורל

קיצי)

Cisza (Akwarela letnia) (13.08.1939) -

Silence (Summer Aquarelle)

שקט - (אקוורל

קיצי)

![]() Tobuł tułaczy 5.02.1939 - A

Bundle of a Vagabond – שק של

נדודים

Tobuł tułaczy 5.02.1939 - A

Bundle of a Vagabond – שק של

נדודים

The Warsaw Ghetto Poems (

From the Book of Irena Maciejewska)

Co Czytalem Umarlym- What I read to Dead

Co czytałem umarłym – What I

Read to the Dead (Polish)

What I Read to the Dead (English)

Posłowie Epilogue (Hebrew) | Notatka

dla pedantów Note to the Pedants (Hebrew) | Do polskiego czytelnika To the Polish Reader (Hebrew)

![]() Wołanie w nocy - A Cry in the Nightבכי בלילה -

Wołanie w nocy - A Cry in the Nightבכי בלילה -

![]() Okno na tamtą stronę - The Window to the

Other Side – חלון

הפונה לצד

ההוא

Okno na tamtą stronę - The Window to the

Other Side – חלון

הפונה לצד

ההוא

![]() Telefon - The

Telephone - הטלפון

Telefon - The

Telephone - הטלפון

![]() Legendy wigilijne - Legends

of the Eve of Christmas – אגדות

ליל חג המולד

Legendy wigilijne - Legends

of the Eve of Christmas – אגדות

ליל חג המולד

![]() Dwaj panowie na śniegu - Two Men on the Snow – שני אדונים

בשלג

Dwaj panowie na śniegu - Two Men on the Snow – שני אדונים

בשלג

![]() Paszporty - The Passports

- דרⳫונים

Paszporty - The Passports

- דרⳫונים

![]() Klucz u Stróża - The

Key is at the Concierge – המפתח

אצל השוער

Klucz u Stróża - The

Key is at the Concierge – המפתח

אצל השוער

![]() Mała stacja Treblinki - The Small Station of Treblinka –

התחנה

הקטנה

טרבלינקה

Mała stacja Treblinki - The Small Station of Treblinka –

התחנה

הקטנה

טרבלינקה

![]() Obrachunek z Bogiem – An Account with God, Warsaw Ghetto 1943 –

חשבון עם

אלוהים

Obrachunek z Bogiem – An Account with God, Warsaw Ghetto 1943 –

חשבון עם

אלוהים

![]() Kartka z dziennika akcji

- A Page from the Diary of the Actions – דף

מיומן האקציה

Kartka z dziennika akcji

- A Page from the Diary of the Actions – דף

מיומן האקציה

![]() Okolice Warszawy - Warsaw

Suburbs – פרוורי

וארשה

Okolice Warszawy - Warsaw

Suburbs – פרוורי

וארשה

![]() Pomnik - The Monument - אנדרטה

Pomnik - The Monument - אנדרטה

![]() Rozmowa z dzieckiem - Talking

with a Child – שיחה

עם ילד

Rozmowa z dzieckiem - Talking

with a Child – שיחה

עם ילד

![]() Nowe święto -

A New Holiday – חג חדש

Nowe święto -

A New Holiday – חג חדש

![]() Ostatnia legenda o

Golemie - The Last Legend about the "Golem" of Prague – האגדה

האחרונה

אודות הגולם

Ostatnia legenda o

Golemie - The Last Legend about the "Golem" of Prague – האגדה

האחרונה

אודות הגולם

![]() Cylinder - A Cylinder

(Top Cap) - הצילינדר

Cylinder - A Cylinder

(Top Cap) - הצילינדר

![]() Wiersz o dziesięciu

kieliszkach - A Poem about Ten "Chalices" (Wine Glasses) – שיר אודות

עשר כוסות

Wiersz o dziesięciu

kieliszkach - A Poem about Ten "Chalices" (Wine Glasses) – שיר אודות

עשר כוסות

![]() Zahlen bitte! - You Have to

Pay Please! – נא לשלם

בבקשה!

Zahlen bitte! - You Have to

Pay Please! – נא לשלם

בבקשה!

![]() Dwie śmierci - Two Deaths – שתי

מיתות

Dwie śmierci - Two Deaths – שתי

מיתות

![]() W ten dzień - At This

Day – באותו

היום

W ten dzień - At This

Day – באותו

היום

![]() Piękna niedziela -

The Beautiful Sunday – יום

ראשון היפה

Piękna niedziela -

The Beautiful Sunday – יום

ראשון היפה

![]() Romans współczesny - A Contemporary

Romance – רומן בן

זמננו

Romans współczesny - A Contemporary

Romance – רומן בן

זמננו

![]() Erotyk anno domini 1943

- An Eroticist Year 1943 - ארוטיקן

שנת 1943

Erotyk anno domini 1943

- An Eroticist Year 1943 - ארוטיקן

שנת 1943

![]() Dajcie mi spokój - Leave

Me in Peace - עיזבוני

במנוחה

Dajcie mi spokój - Leave

Me in Peace - עיזבוני

במנוחה

![]() Bardzo przepraszam - I

Beg Your Pardon - סליחה

רבה

Bardzo przepraszam - I

Beg Your Pardon - סליחה

רבה

![]() Już czas - It's Time - זה

הזמן

Już czas - It's Time - זה

הזמן

![]() Za pięć dwunasta -

Five minutes to Midnight - חמש דקות

לחצות

Za pięć dwunasta -

Five minutes to Midnight - חמש דקות

לחצות

![]() Kontratak (wersja II) -

Counterattack - התקפת

נגד

Kontratak (wersja II) -

Counterattack - התקפת

נגד

Varia - Various - שונות

![]() Résumé, czyli

Krakowiaki makabryczne - Resume of the Macabre Krakoviacs - תקציר

קרקוביקים

מקבריים

Résumé, czyli

Krakowiaki makabryczne - Resume of the Macabre Krakoviacs - תקציר

קרקוביקים

מקבריים

|

2 . Do obwodowego Szmerlinga - To the Square Commander

Szmerling - למפקד

האזורי

שמרלינג |

|

3.

Do mecenasa Wacusia - To the Lawyer Vacuś - לעורך

הדין ואצוש |

![]() Pożegnanie z

czapką - Parting from a Cap - פרידה

מכובע

Pożegnanie z

czapką - Parting from a Cap - פרידה

מכובע

![]()

Selected Poems I (Polish & English)

Selected Poems II (Polish & Hebrew)

Selected Poems III (Polish & Hebrew)

Selected Poems IV (Polish & Hebrew)

Ce

que j’ai lu aux morts…

Szlengel Poetry Translated from Polish to French by Jean-Yves Potel

![]()

What I Read to the Dead (Polish)

What I Read to the Dead (Hebrew)

What I Read to the Dead (English)

What I Read to the Dead (English - in Kobos Web Site "SHOAH")

We Remember Władysław

Szlengel, The Ghetto Poet! We Shall Not Forget!

![]()

This web page was first posted in April 2003, 60 years after the Warsaw ghetto uprising

It was last updated